The tricycle rattled down craggy, unpaved roads, making an occasional splash over remnants of the last rain. Bracing myself against the vehicle’s sudden jerks, I turn my attention to the fleeting scenes of life in a fourth class Visayan municipality. It was the first of what would be a series of extended visits, of long discussions with return migrants about life abroad and life back. As the tricycle staggered on, expanses of rice and sugarcane fields rolled by, an occasional one-story, concrete house providing a break in the landscape. A truckload of freshly harvested sugarcane rumbled on its way to the nearest mill. Rice was spread out to dry on the dirt roads. It all seemed idyllic to my city-bred eyes.

We arrive with sore limbs to a house much like the ones we had passed. A young woman with a smile that had seen hard times rushed to greet me, her catching enthusiasm like a crisp breeze on an oppressively hot day. She was my key informant, and she had offered her place as my base for exploring the intricacies of returning to the countryside after laboring abroad. Nestled amidst rows of towering stalks as far as eye can see, it had the bare comforts that my semi-low-maintenance self required, except that it was an hour from the nearest city, three hours from the provincial capital, and 45 minutes from the only rural health unit (RHU) servicing several barangays. Getting sick, I thought, would mean having to bounce over rough roads – the tricycle being the only means of public transportation – and obtaining only basic medication as afforded by the RHU. While not the most ideal of situations when one is sick, the presence of a health facility, even though no doctors were around, did ease some of my anxiety, which I further drowned with an overdose of vitamins and large swigs of the community’s good cheer.

I was reminded of those days while watching a clip played during the final leg of the Philippine presidential debates. It was of Jun, a youngish man whose world-weary face and gray hair belie his age. He had been among those chosen to represent a sector and pose a question to the candidates. Jun hails from a far-flung village in Northern Samar. Footage of his community reveals nipa and semi-concrete houses ensconced in wooded mountains, a river running through them. The remoteness of his village was strangely reminiscent of my own field site, despite the contrasting terrain. (Or perhaps it was the Visayan link that rekindled the memories.) But the contrast grew starker as Jun told of how the only health facility in the area was always closed, perhaps because of the absence of doctors or volunteers. It was a three-hour walk across the mountain and through the river to the highway, from where they could take a motorbike to the city and the nearest hospital.

He thus tearfully asked: “Ma’am, Sir, what would be your solution to the problem in our area? No doctor, facilities are inadequate, and no medicine. A lot of people have gotten sick, died, in our area, just like my dad.” It happened quite suddenly. His father passed away two days after complaining of a stomach ache.

Behind the idyll of the countryside, the fresh air and the verdant pastures, lies a region steeped in poverty. When the French were staging their many revolutions in the 1700s, landscape paintings depicting peaceful and copious rural environs spread among the ruling classes of England. Denis Cosgrove (2008) notes how these paintings reassured the English ‘squirearchy’ that “all was well with the world.” England had no starving peasants; it was not the mess that was France. But the lowliest of English farmers were being evicted from the land by sheep and by a more rabid execution of the Enclosures Act, where land for communal farming was enclosed as the private property of the lords. The peasants were far from pastorally comfortable. They were starving, fleeing to cities to become cogs in an industrial system; those remaining bled dry by exorbitant rents. Yet, the image of the English countryside as painted in the 1700s has persisted.

As with the English ruling classes, the calm of seaside, the green fields of rice, and the seeming serenity of mountains convince us that the countryside is paradise, or at least a place to strike off our bucket list. That it is in the city (or perhaps in those distant lands in the south) that social ills are rife, and battles against privation fought. But as with England in the 18th century, the rural folk, the agricultural workers, the indigenous people concealed by mountains or out at sea – they are among the country’s poorest. Many rush to the urban centers, to those dense, filthy settlements of iron and cardboard, to smoky leaded air, for work. And while the sorry sight of slums makes us believe that cities and urban areas house the most indigent, they do not. The countryside does, as these numbers show:

In 2006, more than 40% – almost double the urban figure – of the rural population fell below the poverty line, the income needed by an individual or a family of six to survive in a year. The national poverty line then, was P15,000 for an individual. Ten years on and we see only a slight drop, with recent data estimating rural poverty incidence to be around 39%, still above the 26% national average.

Life in the slums is certainly not a bed of roses. And in cities, the income gap between the rich and the poor is wider. But Jun’s concern illustrates how utterly marginal many of the rural folk are, unable to access even the most basic of services. A stomach ache could have simply been a ruptured appendix, a common enough condition that, with speedy treatment, would not be life-threatening. It would have been curable, as many of the illnesses that plague them are, if only there was a doctor, a nurse, a healthcare worker, or heck, an emergency response team to quickly deliver patients to the nearest hospital so they would not have to walk three, six, twelve hours. Those in the city have a greater shot at these amenities. As El Nino blazes through the country, the rural poor are hard-pressed even for food.

The severe deprivation in rural and remote areas harks to the kind of “locational discrimination” emphasized by Edward Soja (2009). Decisions on where to set up economic zones, transportation and communication facilities, social services such as schools and hospitals, and residential and commercial districts, and the subsequent distributional patterns of investments, even NGO interventions, act in favor of certain groups and lead to the spatial concentration of opportunities and of poverty. These decisions are not made in a vacuum. They are products, not mainly of a free market or a benevolent state, but of capitalist expansion, and as such, are predisposed to reorganize space unevenly. In the Philippines, capitalist activities tend to be concentrated in Metro Manila, the capital region, and areas within easy reach of it, such as CALABARZON and Central Luzon. It comes as no surprise then, to find that 62% of Philippine growth remained in these areas. The farther one is from these zones in terms of relative distance – traffic conditions, means of transportation – the more one is left behind.

NGOs tend to exacerbate this uneven development given their embeddedness within global networks, aid chains, and national political structures (Bebbington 2004). Often, interventions lead to the creation of “development hotspots;” unable to reach the furthest or the poorest as the access of NGOs to places and their patterns of involvement depend on their relationship with the state, their funders’ perceived needs, and the probability of immediate results.

The spatial concentration of activities and opportunities imposes biases against certain populations given their geographic location, biases that Soja notes are “fundamental in the production of spatial injustice and the creation of lasting spatial structures of privilege and advantage.” Locational discrimination results in a re-concentration of poverty among the locationally destitute; it promotes inequities between the core and periphery and pushes the marginalized deeper into the margins. A glimpse of the 20 poorest provinces in the country in 2015 further illustrates the advantages of being in the core, and the disadvantages of being in the periphery:

| 1. Lanao del Sur (ARMM) – 74.3% | 12/11. Eastern Samar (Region 8) – 50.0% |

| 2. Sulu (ARMM) – 65.7% | 12/11. Lanao del Norte (Region 10) – 50.0% |

| 3. Sarangani (Region 12) – 61.7% | 13. Mt. Province (CAR) – 49.9% |

| 4. Northern Samar (Region 8) – 61.6% | 14. Western Samar (Region 8) – 49.5% |

| 5. Maguindanao (ARMM) – 59.4% | 15. North Cotabato (Region 12) – 48.9% |

| 6. Bukidnon (Region 10) – 58.7% | 16. Catanduanes (Region 5) – 47.8% |

| 7. Sultan Kudarat (Region 12) – 56.2% | 17. Leyte (Region 8) – 46.7% |

| 8. Zamboanga del Norte (Region 9) – 56.1% | 18. Negros Oriental (Region 7) – 46.6% |

| 9. Siquijor (Region 7) – 55.2% | 19. Zamboanga Sibugay (Region 9) – 44.9% |

| 10. Agusan del Sur (Caraga) – 54.8% | 20. Sorsogon (Region 5) – 44.8% |

None of these provinces are anywhere near the capital. And ten of them have a poverty incidence of more than 50%, which means that more than half of the population in these provinces fall below the poverty line.

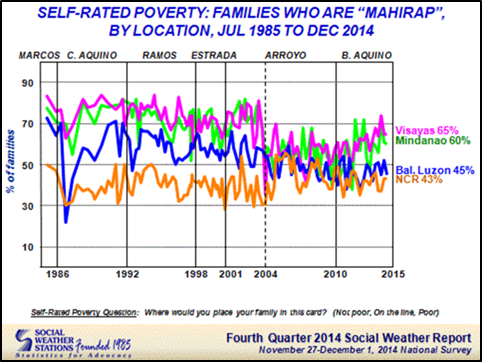

Perceptions of self-rated poverty as studied by the Social Weather Stations in 2014 also echo the idea of locational discrimination, with 65% of those surveyed in the Visayas and 60% of those surveyed in Mindanao identifying themselves as poor, in comparison to 43% in NCR and 45% in the rest of Luzon. Location, and more importantly, the experience of rurality, does seem to be linked to one’s perceptions of being poor.

While historical causes, political conditions, and entrenched patron-client relationships cannot be discounted in the examination of rural poverty, a rethinking of spatial organization may be in order to avoid the pitfalls of locational biases. Despite years of introducing rural development initiatives such as farm-to-market roads; irrigation and agricultural support; and rural jobs, the cycle continues. One can surmise that perhaps, many of these initiatives have also fallen prey to locational biases, making me doubt at times if those in office even know what the peripheries mean.

Jun comes from the fourth poorest province in the country, where the doors of health facilities – if there are any – remain locked, and having PhilHealth, the national insurance policy extolled by one of the presidential bets, an irrelevant matter. Why, after all, would villagers concern themselves with an insurance policy when the onset of an illness rouses far more distress than merely the absence of money for medication entails? Countless times in the farming community that was my research site, scenarios of bouncing in a tricycle for 45 minutes while warding off nausea and agonizing pain flashed through my mind; pre-natal check-ups meant that women had to take bumpy rides to the hospital an hour away, a risk that would have been more fatal to the unborn. And that is not even half as bad as having to walk, cling to someone’s back, or be carried in a makeshift stretcher for hours, over mountains and rivers, slipping on slopes, tripping on twigs or rocks, being tossed by currents. If you get sick, your immediate worry is not the cost, but how you can even manage to trudge to a hospital alive.

It takes someone like Jun to jolt our senses, to tell us that PhilHealth, or any other putative government accomplishment, matters little when it overlooks the realities of people in peripheries no one has heard of. Programs are nice. But a high handed “the government has long had measures in place; it’s a pity you weren’t able to make use of them” attitude reeks not only of the refusal to recognize the plight of those who do not fit into the neat little categories we construct around the poor but also of a self-absorption that creates blinders, making us obsess over results rather than seek to understand the everyday struggles masked by the numbers. No platform is worth bragging about if people continue to suffer forgotten. Numbers are good, but behind the statistics is a face.

In response to Jun’s question, all candidates promised to set up health facilities in every barangay, an encouraging start towards addressing locational bias, as barangays are the units closest to people in isolated communities. But I particularly applaud the simple idea of having a doctor in every barangay. A doctor means that health centers will stay open, or in the absence of a facility, that people’s minds can still be put at ease with an immediate diagnosis and with the assurance that help is nearby.

Featured image taken from this site.

References:

Bebbington, Anthony (2004) “NGOs and uneven development: geographies of development intervention”, Progress in Human Geography, vol. 28:6, pp. 725-745.

Cosgrove, Denis. “Geography is Everywhere: Culture and Symbolism in Human Landscapes” in Oakes, Timothy S. and Patricia L. Price (eds) The Cultural Geography Reader, Oxford: Routledge.

Soja, Edward (2009) “The city and spatial justice”, Space and Justice, vol. 1.

National Statistics Office

Social Weather Stations

USAID (www.usaid.gov)